Bleary-eyed, we raced over the plains of the Masai Mara, the chilly morning air whipping around us as we gripped our thermoses with one hand and the vehicle with the other. Far in the distance, our guide had spotted a cloud of dust rising from a rocky outcropping—to our untrained vision, yet another feature of the vast, otherworldly landscape, but to him, a clear sign of a recent predator chase. He radioed a fellow guide and they spoke in hushed voices to each other. We tried to pick out any familiar-sounding words, but as the car continued forward, our path remained unknown to us, our ignorance of Swahili protecting the mystery.

The car loudly bounced over the rutted tracks as we neared our target. As we approached, we looked eagerly around for any sign of drama: vultures circling overhead, a bloody carcass. Instead, we were greeted with two female lions lying in a bare patch of grass, eyes closed softly in resignation. Confused, we turned to our guide for an explanation. There had been a chase, but it had been unsuccessful, he said. The prey had escaped, and the lionesses were resting, contemplating their next move. A hopeful hyena paced the pathway nearby, but otherwise, the scene was quiet. We sat there in tranquil silence for a few minutes, the early-morning sun casting long shadows across the plains, before driving off to watch the next story unfold. Not every event could be observed or captured, but everything was new to us, and we trusted that soon our guide would reveal something completely unexpected.

Our safari experience traversed Kenya’s Masai Mara and the Okavango Delta in Botswana, two of Africa’s most distinct ecosystems. But the story that emerged anew every day on the plains and in the bush was at its core the same: birth, mortality, joy, and survival, a complex interplay of creature and landscape, with a smattering of humans lucky enough to witness it. As we grew to learn, the animals had their own schedule, carried out with complete disregard for the strange two-legged creatures excitedly watching them. But through it all, our guides were the portals to our entire experience, at once our storytellers and zoologists, our photography coaches, our translators and interpreters, and even our bartenders. In their vehicles, surrounded by the landscapes they knew intimately, we were at their mercy, but we trusted them implicitly as over and over again they led us to new discoveries.

In the few days we had on safari, we managed to absorb a small fraction of our guides’ knowledge, if not their intuitive sense of the ecosystem. One guide taught us that giraffes can see predators from far off and will all turn to look toward one if they see it, and that elephants dislike the scent of humans but will tolerate it anyway. Another let us get out of the vehicle to take photographs of hippos bathing in the river, but told us that the same animals on land were some of the most dangerous in Africa. Despite everything we learned, our knowledge paled in comparison to the vast expertise of our guides, and all we could do was observe in wonder as they led us through the wilderness.

Once, driving through a grassy field in the Okavango Delta, our guide stopped abruptly, directly in the path of an enormous bull elephant. With bated breath, we watched as the bull strode heavily toward our vehicle. I clutched my camera in my lap, scarcely daring to lift it. As he reached the vehicle, he turned his face in our direction. Would he flip the vehicle with his gigantic tusks? I thought. How dare we confront him like this? Holding onto the side of the vehicle, I tried to formulate a survival plan. At last, mere feet away from us, he gave a thundering, irritated snort, shaking his head sternly, ears spread wide—clearly communicating his disapproval at our impertinence. I did not release my grasp on the side of the Land Rover until he turned away from us, my fumbling hands managing to capture a photo of his retreating backside. Our guide, seasoned and secure in his expertise, laughed at the terror on our faces. The elephant would never have attacked, he reassured us. He couldn’t prove it, but he just knew. The elephant’s ways were as clear to him as much as they were a mystery to us, and he could read his body and face like the expressions of a familiar friend.

Later, we parked in an open field as the sun set slowly over the Delta, stepping gingerly out of the vehicle to stretch our legs. Our guide popped up the grill of the Land Rover, laying a gingham cloth over the metal surface. He deftly unpacked tins of cookies, a row of tumblers, and a bottle of gin, pouring out a practiced ratio of alcohol and tonic water and topping our drinks off with lime. It was yet another one of his seemingly-endless talents, honed after hours and hours in the bush each day, sharing his homeland with strangers.

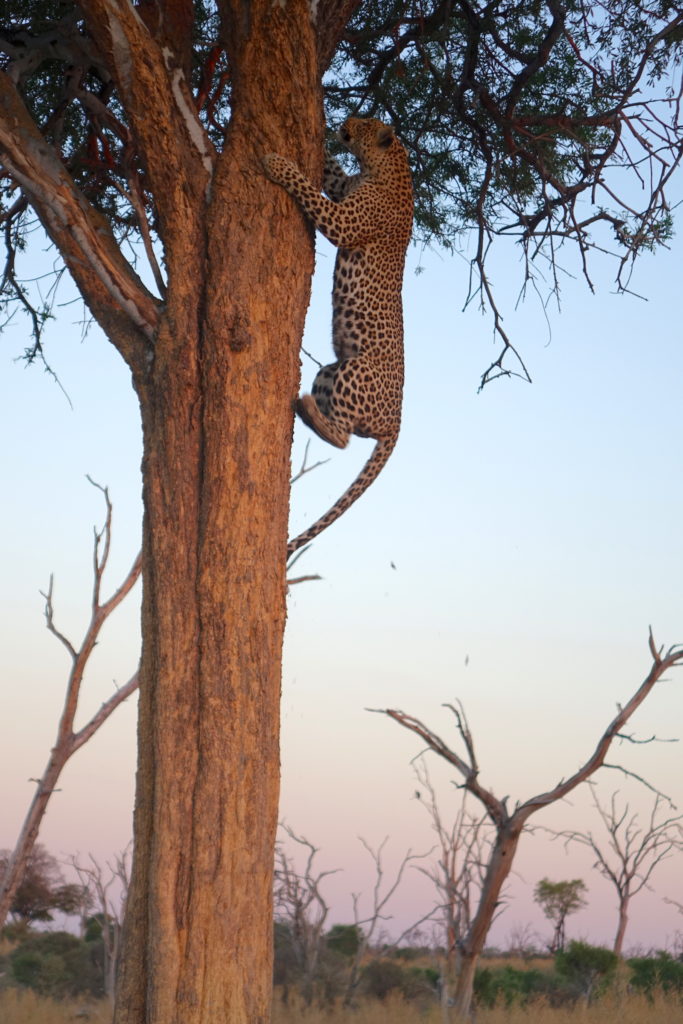

The next day, we stopped in the middle of a dusty road as our guide stepped out of the car to observe a set of barely-discernable pawprints. Hoisting himself back into the driver’s seat, he set off to follow the tracks. They led us suddenly to a female leopard lounging woefully in the shade of a tree, and our guide pulled up expertly next to her at the perfect angle for our photographs.

Licking her chops, she gazed toward the other side of the clearing, where a satisfied hyena had snatched her kill and dragged it under another tree. The hyena guarded the fresh impala carcass, staring at us impassively as we judged him according to our moral standards, even as we realized they were impossible to apply here. After a while of watching the unchanging scene, we decided to drive off toward where a rare pack of wild dogs had just been spotted. The dogs—who, despite their friendly appearance, were more closely related to wolves than to domestic canines—began a pre-hunting bonding ritual. The puppies chased each other, tugging at each other’s ears; the adults sniffed each other purposefully as the alpha couple began to round up the group. Over a period of an hour or so, as the sun began to set, they assembled, cohered, and moved as one organism deeper into the bush. At last, they caught a scent on the air: the freshly-killed impala we had just left. The pack began to run toward their target, and we followed swiftly behind. Before our eyes, the drama played out: a group of dogs rushed toward the hyena, who abandoned the impala and escaped into the bush; another group of dogs surrounded the leopard, who clawed her way to safety atop her tree. The impala met its final destination in the mouths of the gleeful dogs as the leopard watched helplessly, and all we could do was sit quietly and take our photographs.

We had been lucky to see such a story unfold, and marveled out loud at our luck. With a small smile, our guide informed us that he had known all along what would happen, known from the outset that the dogs would pick up the scent of the impala, known who the victors and the losers would be. But it was part of the excitement, he said. He had been a guide for decades, but sharing the experience with guests made it new for him every time. We sat back in our seats, astonished, as he led us again down the path, toward whatever would come next.