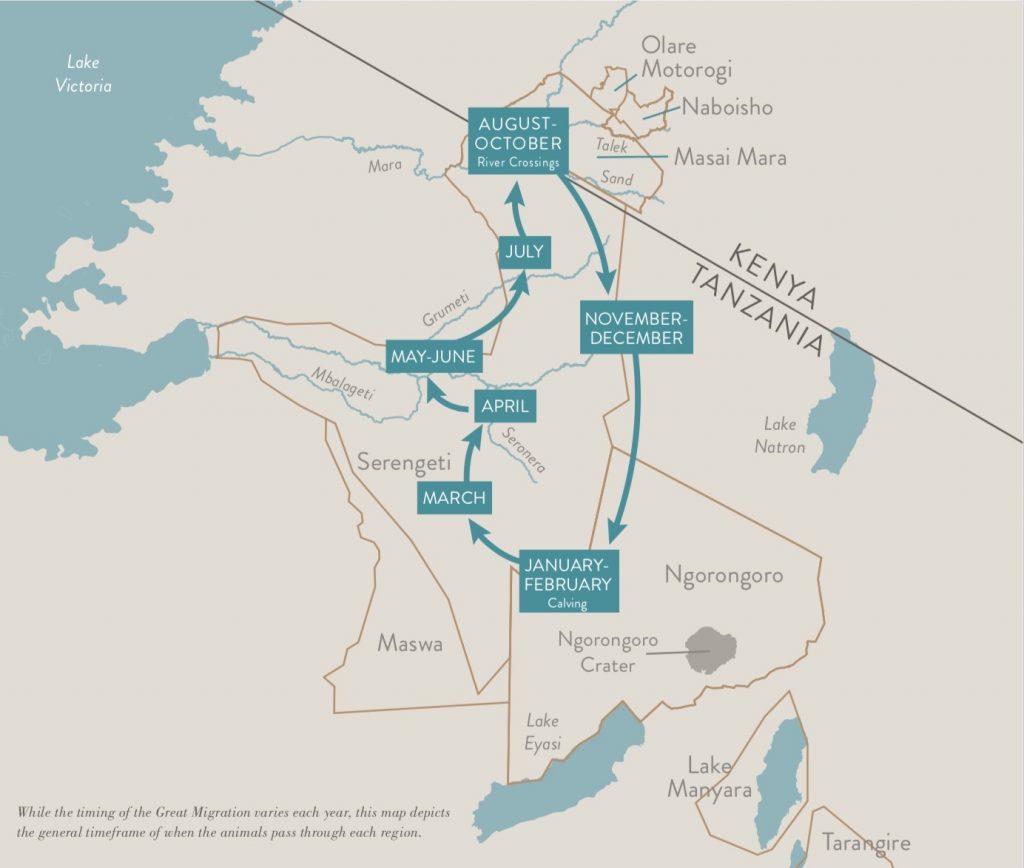

In my first conversation with travelers planning a trip to Kenya and Tanzania, I’m always asked, “When does the Great Wildebeest Migration take place?” Pictures and discussions of the event always make it seem like an annual festival, occurring once a year at a specific time. However, the Great Wildebeest Migration is always taking place. The migrating wildlife just happen to move through different areas of the Serengeti (Tanzania) and Masai Mara (Kenya) during various times of the year.

First, it’s probably helpful to understand that the Serengeti and Masai Mara are the same ecosystem and wildlife moves freely between the two parks. They are identified by different names, but the only thing separating the two is an invisible political boundary.

Second, and before I get too carried away by the Migration, I’d also like to note that both the Serengeti and Masai Mara are worthy of your consideration even when the migration isn’t taking place in a particular area. The Masai Mara and surrounding private conservancies remain some of my favorite and the most productive areas for wildlife viewing during the “shoulder season.”

For most, when asked to conjure images of what the Great Wildebeest Migration consists of, one often sees images of wildebeest leaping off a massive riverbank into crocodile-infested waters, risking their lives for the infamous “River Crossing.” This riverbank is the Mara River in the northern Serengeti and Masai Mara Game Reserve. But there’s more to the Migration than the River Crossing and the carnage tied to it. For the sake of simplicity, let’s start chronologically with the beginning of the calendar year during a “typical year,” one without major droughts or weather pattern changes that can throw off the migration timeline.

January – March

In a typical January, the Migration is in the short grass plains of the southern Serengeti and the Ndutu area of the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. This region is extremely photogenic, with wide open grasslands and often a lone acacia tree sitting unaccompanied by its noisy friends for most of the year. The area is rich with nutritious grasses, and the conditions are ideal for birthing and raising their newborn calves. It’s the short rain season, and the color contrast of the green grass serving as the foreground to blue skies and thousands of animals in your view is astonishing.

Often an underrated time of year to see the migration, it is my favorite. It’s when expectant mothers are readying to drop their calves (typically in February and March) and all the animals seemingly look better fed and less stressed. The wildebeest can hold their babies in their wombs until the opportune moment (past their gestational period if needed), playing the numbers game with predators. If they all drop their calves at the same time, there’s simply more “supply” than “demand” for food, thus increasing the odds for survival. Some 400,000 calves are born in a span of 2-3 weeks. For me, this is the true miracle of the Migration.

Shortly after calving, the massive herds of wildebeest will slowly start to drift northward. What drives this primal need to migrate is based on resources; but what actually tells the wildebeest “it’s time to move” is still not scientifically proven. It’s most likely some combination of the rains, humidity, barometric pressure and lightning in the distance. It’s said that wildebeest can sense rains from over 30 miles away. From my observations in the field, wildebeest are not the cleverest animals and it simply takes one to move in a single direction to move thousands behind it. But not all the wildebeest will follow at the same time. The Migration is comprised of many separate movements of wildebeests as they make their way towards greener pastures. The wildebeests are accompanied by hundreds of thousands of other ungulates (hoof stock), including gazelles, zebras, and eland. They mow down the grasses at differing levels based on their size, leaving nothing but stubble and dirt behind as they journey onward.

April – June

In April, the momentum is gaining, and the movement of the migration starts to head northwest towards the Western Corridor. Sometime around May, the masses arrive in the area and start to push towards the Grumeti River. Though not quite as spectacular as the massive precipitous of the Mara River, the herds must cross the Grumeti River to continue their journey northward. The crocodiles of the Grumeti are equally keen for a meal as their brothers in the Mara River, and this can be quite a spectacle to witness. If you have the budget to stay in the Grumeti Reserve within the western area of the Serengeti, this 300,000 acre private reserve operated by Singita will give you the most exclusive access to the Migration. By June, this area is at its peak with the migration in full swing.

July – October

Sometime around July, the migration continues northeast towards the northern Serengeti’s Mara Sector (and the nearby Lamai Wedge), spilling into the Masai Mara to the north. The wildebeest will remain here, grazing, for much of August through October, and this region is synonymous with the most action. Along with northern Serengeti, this is the time of year to be Kenya’s Masai Mara for the migration. The banks of the Mara River are intimidating, and the wildebeest and zebra will leap off, wide-eyed, out of desperation to make it to the other side. Unlike the birthing during February and March, this is a time of death and carnage. It’s not uncommon to see crocodiles feasting on unfortunate victims and to smell and see the carcasses as they float downstream. It’s nature at this most unforgiving and a thrill that many of our clients wish to experience.

November – December

By November, the masses sense the arrival of the long rains and gradually make their way south. They pass through some of the most spectacular areas of the Serengeti, including the central Seronera area. The massive granite outcroppings known as “kopjes” are a visual stunner, and if you can tolerate the rains, this time of year will allow you to experience both the migration and the most beautiful areas of the park sans tourists. With the right guide, November in central Serengeti can be magical.

Around December, the cycle will be complete with the arrival of the herds into the short grasslands of southern Serengeti and the Ngorongoro Conservation area.

I’ve traveled to Kenya and Tanzania during different seasons, all of which were spectacular and rewarding in their own right. Regardless of the rains or where the migration may be taking place, with the right set of expectations, guides and location, it’s hard to go wrong with a safari to Kenya or Tanzania.